Key Takeaways

- Senior living’s penetration rate remains low, and some operators are launching targeted, branded product lines to capture new customers

- Operators are creating new brands based on price point, acuity, geography, lifestyle, with mixes therein

- Among pricing models, the middle market is the most challenging to define and, as such, filled with promise

- Operators are taking cues from the hospitality industry in how to execute a multi-brand strategy

- The sweet spot for senior housing is around four brands

Embrace a multi-brand strategy to capture new customers

The impending wave of baby boomers into the senior population will bring more than just massive numbers of potential residents. This isn’t merely a question of bulk. It’s a question of breadth. As boomers age into senior living, they will be healthier than their predecessors. They will live longer. They will, by virtue of their generational profile, exhibit more discerning tastes.

They will be trickier to serve.

Kai Hsiao, CEO of the Portland, Oregon-area Eclipse Senior Living, has a term for this trickiness: the unspoken 88.

That’s 88 as in 88%, the approximate percentage of seniors not yet living in senior housing. In June of 2018, the National Investment Center for Seniors Housing & Care (NIC) showed an occupied penetration rate for the 99 primary and secondary senior housing markets at 9.1%.

That same year, a report from Newport Beach, California-based real estate research firm Green Street Advisors showed senior housing penetration a bit higher, at 11.7%. Green Street projected a possible dramatic rise in 2025 that would still only be 12.5%.

Even if penetration were to jump even higher to 15%, that still leaves 85% of seniors outside senior housing. And it leaves industry leaders wondering if they need to offer additional products.

“You have 88 to 90% of the market that hasn’t found anything that appeals to them yet,” Hsiao says. “So what are they looking for?”

The solution gaining steam is a growing business model: the multi-brand strategy. Senior housing operators are following the lead of the hospitality industry by building new product lines as separate brands, and even sub-brands. These brands target consumers in different ways, some by price point, some by acuity, some by geography, some by lifestyle.

The goal of developing these new branded products is to capture an untapped consumer base and build new revenue streams. For his part, Hsiao is drawing from his experience in hospitality and his time in senior housing to build what he calls a “family of brands” under the Eclipse banner. Eclipse currently has two brands: Embark and Elmcroft. Both are middle-market products, Embark for low acuity seniors, Elmcroft for high acuity ones.

Eclipse then plans to add two luxury lines, one for low acuity and one for high acuity, thus giving it a quadrant of brands to capture different consumer types.

“Not all seniors are built the same — they have different wants and needs,” Hsiao says. “We are in a world of personalization. We are in a world of customization. I think as we begin to evolve as an industry, we need to speak to different segments of the population. Baby boomers aren’t just one big bucket. There are segments. And we need to be able to speak to different segments of that bucket.”

Brand segment types

Branded product lines within the hospitality industry are broadly diversified, with brands and sub-brands built to attract customers based on their specific needs and desires.

These can include customers driven by cost, ones who care about style of building (such as a large property versus a boutique), ones who care about being comfortable over an extended stay or ones who are attracted to a lifestyle offering, like a hotel catering to customers who want to explore a city as tourists, or ones who want a focus on wellness.

While senior housing is a long way from being as diversified in its offerings as hospitality, it is expanding. Senior housing operators today that launch new brands targeted at new consumer segments define their offerings by one of four traits:

- Price point

- Resident acuity

- Geography or environment

- Lifestyle

The desire to not merely capture seniors but to attract them, specifically boomers, is at the heart of today’s burgeoning brand expansion. And while there is diversity in their methodology, there are similarities in the results, the first of which is the most popular choice by which to brand: price point.

“Ideally, you would have three (brands),” says Dana Wollschlager of Plante Moran. Wollschlager views the key segmentation for senior housing to be built around three consumer incomes:

LOW-INCOME: for individuals at or below 30% of the area median income

MIDDLE-MARKET: for individuals slightly above 60% of the AMI, but ones who cannot afford to pay an entrance fee and a high monthly fee

HIGH-END: for the “ultra-rich” — individuals who can afford a significant entrance fee, perhaps $500,000 or more, along with a monthly fee of $2,500 to $5,000

An operator’s approach to developing another brand at a different price point depends first of course on what price points it is already serving. Next comes the challenges of branching out into others. Here are the advantages and challenges operators are seeing in developing communities for high-end, middle-market and affordable consumers.

BRAND SEGMENT TYPE: PRICE POINT

Strategies for developing high-end

Advantages: One of the challenges in developing senior housing brands to serve either the middle-market or the affordable segment is that while the rents are lower, the costs of labor, construction, operations and upkeep are fixed. With high-end, luxury products, operators can swing for the fences to deliver an unmatched lifestyle experience to a monied clientele.

Maplewood Senior Living has two brands, both of which are luxury: Maplewood-branded communities, and the new Inspir brand. These are rental communities, with no entrance fees. The differentiating factor between them is location: Maplewood-branded communities are suburban, while Inspir, starting in Manhattan, are urban.

“Our focus and our philosophy is … exceeding expectations, and that drives the luxury component of what we do,” says Gregory Smith, President & CEO of Maplewood and Inspir. “Our brand targets people that are looking for certain expectations. And I think the word ‘luxury’ is part of the fabric of our DNA, and because of that, we have a reputation for providing an exceptional living experience.”

Maplewood is co-developing Inspir with Omega Healthcare Investors. Steve Levin, an Omega senior vice president, anticipates a copycat trend among leading operators who will want to match Inspir’s urban luxury model when they see it successfully bringing in huge rents.

“Once those buildings are open and people are spending $15,000 to $18,000 per month or more, you’re going to see the major operators, the so-called ‘big boys,’ try to do this in an urban setting, delivering a very high level of services,” Levin says.

Challenges: In a way, luxury brands are the simplest to develop from a price point perspective. The clientele is private pay, and perhaps the biggest challenge is securing the real estate. The larger challenges are two-fold.

First, there is the percentage of seniors that can afford a luxury lifestyle, and then within that, the percentage that wants to spend top dollar on rents, as opposed to something a bit more affordable that creates more financial flexibility for other expenses, be they medical, travel or bequeathments.

Second, there is the challenge of coaxing wealthy seniors into a senior housing community to begin with.

“A lot of people we work with who have a lot of money, they want to stay in their homes,” says Signe Gleeson, founder of ElderCare Solutions, a senior housing consulting firm 45 minutes west of Chicago that advises seniors and their families — about 50 to 60 clients per year.

Gleeson sees what many have seen: that the potential residents of luxury senior living can eschew that option in favor of using home care and smart technology to transform their home into a site for aging in place. The wealthy seniors from colder climates might also be inclined to embrace the snow bird lifestyle.

From her vantage point, Gleeson recommends two areas of development, each of which would cater to wealthy seniors with health concerns that negate their ability to either live at home or live in IL. The first is independent living that allows people to enter with a private caregiver. The second is luxury assisted living for people of “significant means” but for whom staying at home is not an option.

BRAND SEGMENT TYPE: PRICE POINT

Strategies for developing middle-market

Advantages: Pathway to Living’s first approach to developing branded product lines was to halve its assisted living offering. Pathway established Aspired Living as a price leader, targeting consumers who can and want to pay the top 10% of a given market’s lease rates, and then dialed that down for Azpira, seeking consumers comfortable with the top quartile.

“We didn’t want to dilute one brand with multiple entry points into the market that aren’t co-existing, so here we have two points of entry into the marketplace that both have a different purpose from a facility perspective, but meet the same health care standards,” says Matthew Krummick, director of real estate development at Pathway. “You can think of it as the Mercedes and the Infiniti dealer down the road. It still offers a great product, but it’s substantially less than the Mercedes.”

The company is doing this by economizing its space and its footprint, using multi-purpose rooms and more common areas with fewer amenities. Those are the areas to trim cost, Krummick says, because the company never wants to scale back on care, while the cost of construction and land remain unbending.

Scaling back amenities and design extravagences is also a strategic necessity to capturing the middle market. Wollschlager views this consumer as a senior with too much income to qualify for a tax-credit community, but not enough to afford a steep entrance fee and monthly payment.

“That is going to be a number of older adults in the very near future, certainly in the baby boomer group,” Wollschlager says.

It’s essential, then, for operators to develop a product that not only costs less, but makes tough choices about where to cut. This includes the visual touches that inherently signal luxury upon first sight.

“You have to value engineer things for (a given) segment,” Hsiao says. “It’s being smart about who you are and being true to who you are. It goes back to, ‘Could we have a glass-cascading waterfall in the lobby?’ Sure. But is that speaking to the audience you’re going after? You can scare people away.”

Challenges: The major challenge to developing a sustainable, middle market senior housing brand are the fixed costs of labor and capital expenditures. While high-end is carved out and affordable is clear too, the middle market remains nebulous, with experts defining it as they go.

“No matter what market you are, the minimum wage is not that different,” says Shankh Mitra, CIO of Welltower. “From a labor perspective, the margins are very difficult with the same service. So the middle market problem will be solved using more technology (and a)lighter touch.”

Mitra sees a need for operators to get creative in their approaches if they wish to succeed in the middle market. The technology component is big because smart home technology can create new efficiencies in operations by assisting staff members with some of the more rote aspects of the job.

“I don’t think that anyone has cracked that code yet,” Mitra says about the middle market. “But that’s something that people are working on.”

BRAND SEGMENT TYPE: PRICE POINT

Strategies for developing affordable

Advantages: The biggest advantage to affordable housing might be the need. Data in 2016 from the U.S. Census Bureau shows homeowners aged 65 and older have a median income of $39,823, by far the lowest total of any age group.

Data that same year from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) showed that U.S. seniors aged 66 and up face the 7th worst poverty levels among seniors in the OECD’s 36 member countries.

And a 2019 study by the Retirement Living Information Center found that while 75% of baby boomers feel that their retirement savings will let them live comfortably, only 35% of generation X feels the same.

All of these trends are pointing the way toward a segment of the senior population that will require affordable housing.

“We do believe that there is a much broader population that we can serve, and there is a real business model,” Mitra says. “No one has succeeded yet, but … I’m confident that (the industry is) going to get there. This is what we’re thinking about 24/7: how do we lower the cost?”

This is where not-for-profits can carve out a niche, says Julie Murray of Shoreview, Minnesota-based not-for-profit operator Ecumen. While bigger operators and for-profit operators tend to have an advantage in rolling out new brands due to their economies of scale, nimbleness and capital resources, not-for-profits still excel in the affordable realm because of their focus on that segment.

“Typically for our communities, 25% of the people we serve are subsidized,” Murray, Ecumen’s senior vice president of sales & marketing and chief business development officer, says. “We have a lot of affordable housing, (and) are looking at how we find that balance to ensure that people are looking at what they need and are able to afford it.”

Challenges: The challenge here is financial, both in terms of financing projects and in terms of the consumer income levels, which affect whether a senior qualifies for the Low Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) program.

Wollschlager offers the example of a resident she’s worked with who exceeded the income limit by just $800. This knocked the person out of affordable housing but also made middle market challenging for them. That kind of challenge making the math work knocks out Minneapolis-based Ryan Companies from this area, too.

“We don’t do any affordable — the model is too hard to finance,” says Eric Anderson, VP of real estate development at Ryan Companies, which works in construction, real estate development, capital markets and property management. “The capital partners require such a return on these things compared to apartments, retail (or) multi-family, because you typically have a two-and-a-half year timeframe to get these leased up.”

To help facilitate the affordable sphere, underwriters might first have to see success, potentially creating a chicken-egg challenge.

“A lot of what is being built today is being dictated by what has been successful in the past, which makes sense,” Hsiao says. “It’s going to take more effort and time to convince folks in the … finance world to sign off on something that is outside of their comfort range.”

BRAND SEGMENT TYPE: ACUITY LEVEL

Memory care: While the templates for independent living and assisted living are fairly clear cut, there is a bit more creativity with memory care, leading to branding around that service. Pathway to Living has a branded memory care program called A Knew Day®, Leisure Care’s memory care program is Opal, while in the suburbs of Chicago, Gardant Management Solutions of Bradley, Illinois, offers White Oaks. These communities exist at different price points, because the brand is the memory care offering, not the cost.

“You have to know why you’re expanding and why you’re diversifying, so you don’t have an identity crisis,” says Julie Simpkins, chief development and engagement officer of Gardant.

Active adult: The more interesting care level branding opportunity is active adult, which potentially exists in an operator no-man’s-land between senior housing and all-ages.

Senior housing is now beginning to move into active adult, with operators viewing it as another revenue stream and a potential bridge that moves younger seniors into IL.

In late 2019, Pathway to Living plans to add a third brand to join Aspired and Azpira: an Active Adult line, which it views as an ideal complement to its current offerings.

BRAND SEGMENT TYPE: LOCATION

One of the keys to success in developing senior housing brands is developing sub-brands based on secondary segmentations. Maplewood’s work with Inspir is a perfect example. The Maplewood luxury brand is built for a suburban clientele, so the company is branding Inspir for urban-focused clientele.

This is one approach to developing senior housing products based on location, whether tailored to a marketplace, or tailored to a developed environment, i.e. urban, suburban or rural.

“The way you have to look at Maplewood Senior Living (is that) the parent organization is broken up into different lifestyles,” Smith says. “It’s almost like, ‘a little bit country, a little bit rock and roll.’ It’s suburban living vs. urban living. In both of those markets, luxury senior living is the core of who we are … (and) we look at the market and let the market dictate to us what we develop there.”

When Omega purchased five buildings in Manhattan in 2015, it partnered with Maplewood to co-develop what will be the Inspir building. They saw a need for senior housing in Manhattan, and used the experience to create the Inspir brand, which they can then transfer to other urban centers. But the luxury component remains the same between the two brands.

“I think when you look at Maplewood and you look at Inspir, you can kind of put them on the same level,” Smith says. “It’s not that one’s a Fairfield Inn and one’s a Ritz-Carlton. They’re both brands on the luxury spectrum.”

BRAND SEGMENT TYPE: LIFESTYLE

When Leisure Care set out 20 years ago to brand one of its offerings, it settled on the concept of “fun.” No matter one’s health, faculty or physicality, all seniors wanted to enjoy their time in senior housing.

With that in mind, Leisure Care began developing brands based on the idea of determining the meaning of “fun” to each segment of its consumer base. The company has umbrella brands, and then sub-brands within those, explains Executive Vice President Greg Clark. These include:

Five Star Fun: IL and AL communities fall under this umbrella, including the Fairwinds brand, which has 11 locations across Arizona, California, Idaho, Missouri, New Mexico and Washington. This was Leisure Care’s first umbrella brand, and serves a lower acuity population.

Better Than Ever: Higher acuity AL communities fall under this umbrella, along with memory care. A “Better Than Ever” community focuses on “fun” through the prism of maintaining good health: “excellent, fun delivery of AL services,” Clark says.

Signature Series: This name is being used internally, based on the concept of fun within the framework of a community that is “elegant, but never stuffy,” with an elevated service level. The brand is being applied to a 24-story high rise IL/AL/MC community in downtown Seattle, called Murano. “Fun for them may be a symphony and the theater and the arts, but we’re still going to make a big deal out of the Seahawks games,” Clark says.

Along with “fun,” another lifestyle senior housing can brand around is “wellness.” One organization doing just that isn’t in senior housing at all. In February of 2019, luxury wellness-focused resort company Canyon Ranch announced plans to launch a senior housing brand built around wellness.

That move might be a bellwether for senior living: learn from hospitality. or prepare to confront their presence.

Cooperatives: Another lifestyle play to capture younger seniors is the cooperative. This is a for-sale product that comes with built-in communal responsibilities, a trait prized by its target owners, who want to be active members in a community structure.

Both Ecumen and Ebenezer in Minnesota offer cooperatives; Ecumen’s is branded as Zvago, which it developed as a response to the realization that the average move-in age was rising while length-of-stay was falling.

“People in Minnesota were very interested in that next move after their big home, (and) were interested in getting rid of the multi-level living … but they didn’t need meals or housekeeping,” Murray says. “There was a strong desire toward ownership … so we looked at what was a type of living that we could help provide for those independent seniors who wanted to move out of their homes into something easier.”

Ecumen launched its first cooperative in 2017 and has built two more since, with two others beginning construction this year. One, in Duluth, will be on land adjacent to an Ecumen CCRC, which sits on (eight) acres and offers 99 units of IL, 60 AL/MC and a 60 units of transitional care.

Ecumen purchased the adjacent (two) acres “proactively,” before they knew how they would use it, but knowing that they wanted the land next to the CCRC, “which turned out to be a good idea in hindsight,” Murray says. The company views the cooperative as a potential resident pipeline for the CCRC, betting that these cooperative owners will want to stay in Duluth as they age.

Lessons from Hospitality

It’s been seven years since Smith started thinking about pouring Maplewood’s existing offering into a new urban brand. This would be the first step toward a multi-brand strategy for Maplewood.

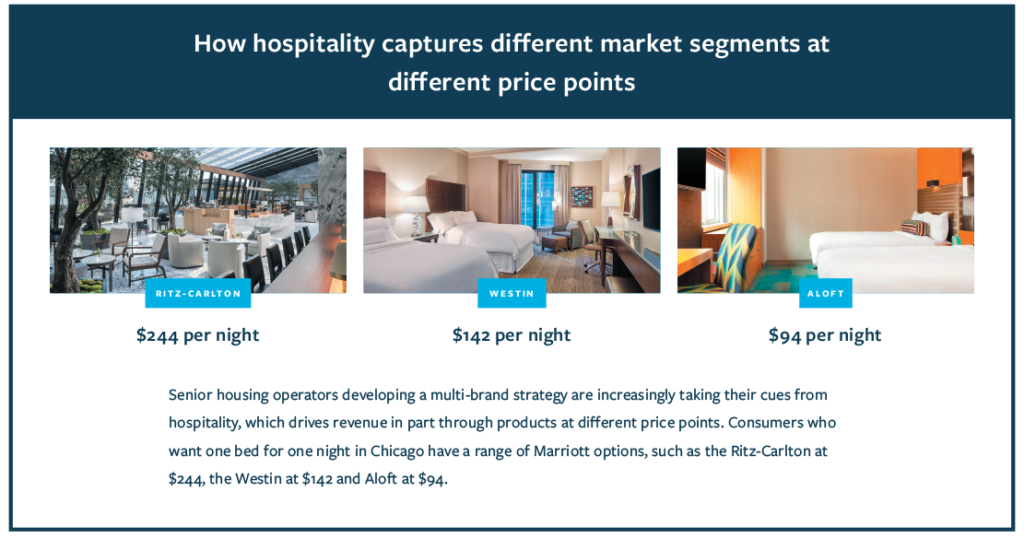

Smith looked specifically at Marriott International, and saw the success the hospitality leader had with its brand diversification, from Ritz-Carlton at the top to less expensive product lines like Aloft toward the bottom, and a range of popular products in the middle, including well-known brands such as Sheraton and Westin.

These brands can co-exist in one market — in fact, that is one of the prime benefits. In Chicago alone, for example, Marriott offers 21 hotel choices. As Smith saw, everything Marriott does is targeted at a specific market and a specific demographic, always with a focus on one word: expectations. Branding, he realized, was all about identifying consumer desires and, most importantly, expectations.

“I took a cue from the hospitality industry and said, ‘Why can’t we do the same thing?’” he says. He’s not alone. As more senior housing operators embrace a multi-brand strategy, they will find valuable lessons from the world of hotels.

The following content reveals the six most important.

HOSPITALITY LESSON #1:

Develop a brand map

Marriott’s acquisition of Starwood Hotels & Resorts in September 2018 boosted the company’s portfolio to 31 brands, divided into five umbrella categories. These categories, subsequent sub-categories and the hotel brands form Marriott’s brand map.

Other hospitality leaders follow the same model: brands based on price, service, length of stay, developed environments and other significant segmentations.

Building these maps works for senior housing, too. Eclipse has already visualized its future brands within the context of a map, one based on differentiations in income and acuity.

Senior housing is unlikely to ever be as stratified in its brands as hospitality. Yet by building what Hsiao calls a “family of brands,” a senior housing operator can turn what might seem an enormous undertaking into something manageable.

“To go back to hospitality, whether it be Starwood or Marriott or Hilton, when you look at the (brand) count, it’s pretty big,” Hsiao told Senior Housing News in 2018. “But they make it manageable by putting them into brands or sub-brands, and I think by doing that you make the big smaller and a little more focused.”

Below are the brand maps for Marriott International and Eclipse Senior Living. Even though Eclipse has nowhere near the brand count of Marriott, its approach to segmentation is the same, so that when the company adds a new brand, it envisions the brand’s position on the map:

HOSPITALITY LESSON #2:

Use economies of scale to your advantage

One of the best advantages that major hospitality companies have when building new brands are their built-in economies of scale — that is, the increased efficiencies and lower cost that comes with grouping like tasks across a diversified business.

“The Hiltons and Marriotts of the world get the benefit of using one centralized support center, so they don’t have to build different support centers for the different brands, and they’re all tethered to the multiple brands,” Hsiao says.

For example, all Marriott International hotels use the same reservation system, at marriott. com/reservation. If a consumer wants to stay at a Marriott brand property in a given city, she goes to that one site and enters the destination and dates. She can even sort based on brands, but this isn’t required, and when she clicks “find hotels” the site locates all Marriott hotels, regardless of brand.

That creates an easier web experience for the consumer, but it also creates a streamlined backend for Marriott, which now only has to manage one website instead of 31, or even five. Some Marriott properties retain individually branded sites, such as Ritz-Carlton with ritzcarlton.com, yet the reservation process on that site ultimately leads back to marriott.com.

HOSPITALITY LESSON #3:

Pretend your customer is transient — satisfy them constantly

Length of stay is a constant focus within senior housing, but as of 2015 the average length of stay in independent living was 1.8 years. That same year, the average length of stay in hotels for overseas guests was 9.7 nights, so domestic guests likely have shorter stays.

As such, hotel staffs make a special effort to constantly satisfy their guests, something senior housing must do as well. This is true any time, but especially with new brands, when operators are trying to rope in new customers.

I think sometimes in our industry, a staff can become too comfortable because the residents live there.

— Greg Clark, Executive Vice President of Leisure Care

“I think sometimes in our industry, a staff can become too comfortable because the residents live there,” Clark says. “An example would be, in some communities, we know what the residents wants for breakfast, so they may not be asked. One of our strong focuses is to make sure to ask and present the options to people. We need to always keep great customer service in mind.”

HOSPITALITY LESSON #4:

Go beyond demographics — embrace psychographics

Building a new brand should not be done without knowledge of the consumer. Most of the experts interviewed for this report spoke about the importance of studying demographics to know what sort of brand to add, and in what market.

Welltower, for instance, has a 17-person data analytics team studying consumers and markets in order to determine where to develop based on an understanding of the customer for whom they are building. Mitra notes that while the use of data analytics to determine a new product might be new to senior housing, it is commonplace in Corporate America.

“American Express somehow knows who to send a platinum card versus who to send a blue card,” Mitra says. “How do they know that? It is very much a psychographic analysis.”

That word, psychographic, is a key differentiator in the market research process, and a crucial tool that some senior housing operators are using as they develop brands. Demographics is the study of people based on raw traits of the population: age, race, income, education, and so on.

American Express somehow knows who to send a platinum card versus who to send a blue card. How do they know that? It is very much a psychographic analysis.

— Shankh Mitra, CIO of Welltower

Psychographics looks at demographics within the context of a person’s psychology: how people behave, not just what they are. Welltower’s team studies both demographics and psychographics in order to capture a vision of the consumer. The risk of only studying demographics is, as Mitra notes, focusing only on a senior’s age and not on his health, or focusing on income and not on spending habits.

“If you’re just looking at age and income, you might get the wrong person, (or) a lot of the wrong people,” Clark says. “You might get people with money who don’t like to spend it. They’re strong savers who want to leave it to their children. If you go into that market with a very high-end offering, it probably won’t do great.”

Leisure Care employs a host of techniques to study psychographics of a potential market, but none more important than on-the-ground research. The company aims to get a feel for a community by digging into resident characteristics at the level of zip codes and even households, all to capture lifestyle and purchasing patterns.

Today, Leisure Care uses a more sophisticated set of systems, but one old school approach that still pays dividends is studying a community’s grocery stores. Clark looks particularly at produce, dairy and alcohol. He looks for fresh gourmet cheese versus packaged products. He looks at the butcher’s counter and checks for fresh fish versus fish that is brought in out of the market. He counts the number of types of a single food item, such as mushrooms, are being sold. He looks at the wine selection.

“Grocery stores don’t have high margins — they have to move that product,” Clark says. “And the mindset of a person looking for those (high-end) things … will be different than the mindset of a person buying a lot of packaged goods, lower cuts of meat, and that type of thing.”

Along with the products, Clark looks at the advertising within a grocery store. A supermarket that messages to its customers by promoting sales, i.e. cost savings, views its customers differently than one that messages by promoting health and wellness. All of this information helps Leisure Care determine its customer as it explores new brands.

HOSPITALITY LESSON #5:

Find the brand sweet-spot — and make each brand clear

As noted, one major difference between hospitality and senior housing in terms of branding is length of stay. Additionally, hospitality must serve paying customers as young as 18 years old, all the way up to the elderly. It is unlikely that any senior housing operator will have a brand map with the stratification of Hilton or Marriott.

The question, then, is the sweet spot. Conventional wisdom is around four, with divisions based largely around income and acuity. An operator branding just based on income would have three brands, while one branding just based on acuity level might have four, including active adult.

And then of course there are sub-brands beneath those categories. Hsiao anticipates Eclipse adding two more in addition to the two high-end offerings it is planning. Wollschlager sees “niche housing” as a fourth product independent of income, such as communities aimed at specific affinity groups.

“I think a sophisticated developer and operator is going to have two to four brands within their wheelhouse,” Krummick says. “I would say, as someone who was once in the hospitality industry, there are far too many brands out there. We had 18 different brands and they crossed over in so many different ways.”

HOSPITALITY LESSON #6:

Keep your brands separate

One of the allures of multi-brand strategies is the economies of scale, and the sense that simply creating a new brand can create a new revenue stream. But operators would be wise to be aware of their own skills and areas of expertise.

“The operators, especially at the regional level, who touch our IL communities don’t touch our AL communities,” Hsiao says. “It’s a different skillset. And if you try to blend them together, you can get a little confused, and then things like margins begin to compress on you.”

Hsiao notes that the margin for a business travel hotel is different than a luxury hotel. “The Waldorf has a different margin level than the Hilton Garden Inn,” he says. “When you have the same management oversight for both, you get a lot of margin compression. They start operating the same, and pretty soon you have one big hot mess on you. If you are going to have multiple brands, you need the discipline to having an understanding of who works on what, and keeping those lanes separated.”

The future

As with every area of senior housing, the influx of baby boomers is changing the way operators think about its products, and how separate brands can impact revenue. Whether segmenting based on income, acuity, geography, lifestyle or some combination, an operator that can successfully deliver multiple brands will have an inside track at capturing a greater percentage of a senior population that is both larger and more diverse than ever before.

Understanding that diversity is crucial. What leaders in hospitality have long understood is that people seek different hotels for different needs and desires. The senior housing population will never be as large as the hospitality population, but it is becoming proportionally diversified in terms of product needs.

How that diversification evolves is the next question. Certainly one addition catching on is senior housing operators adding active adult to the portfolio, giving them an opportunity to potentially keep a resident under their umbrella for 30 years or more. And there are opportunities to continue to develop new senior housing brands based on geography and lifestyle.

Operators not yet prepared to build a family of brands must still be aware of the underlying factor driving the multi-brand strategy, and that is penetration rates. At the end of the day, what matters is tailoring a senior housing product to a specific segment of the senior population to attract new residents who have not yet found what they are looking for.

No matter how this plays out, operators that want to succeed within the boomer landscape will find that just offering the same old senior housing will not be enough.

That broad range of expectations (is something) we not only have to accommodate — we have to get in front of it

— Gregory Smith, President & CEO of Maplewood Senior Living and Inspir

“That broad range of expectations (is something) we not only have to accommodate — we have to get in front of it,” Smith says.

“If we don’t get in front of it, we’re going to be behind it. Over time, as seniors become more technologically sophisticated, and as baby boomers age and are accustomed to certain things, their expectations of what they want are going to be even greater.”