Conventional wisdom states that consumers are attracted to shiny new senior housing product that has flooded certain markets in recent years, putting older properties at a disadvantage and eroding their occupancy.

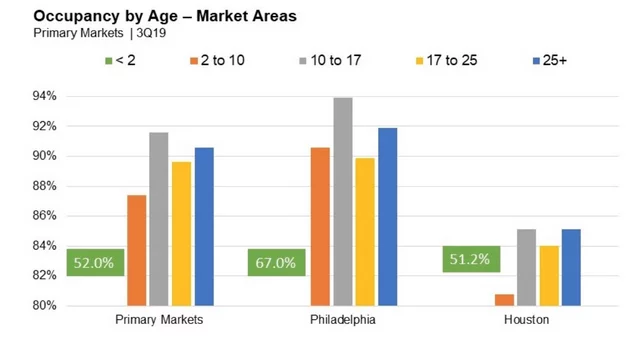

This is not necessarily the case, as statistics show that top-performing senior housing properties tend to be between 10 and 17 years old. However, the data also show that U.S. senior housing properties in primary markets are on average are 21 years old. This is past those years of prime performance, lending credence to concerns that obsolete buildings — perhaps even more than oversupply — are a major problem facing the industry

Given the combination of aging stock and increased new development, it’s increasingly crucial that capital expenditures are made in a timely way and that communities take larger repositioning projects or even find alternative uses for aging buildings.

The good news is that the current financing environment is favorable for these types of projects, but the bad news is that too many communities — particularly nonprofits that have served their markets well for many decades — may still be dragging their feet.

Buildings, markets maturing in tandem

There is a relationship between a building’s age and the maturity of its market, National Investment Center for Seniors Housing & Care (NIC) Senior Principal Lana Peck told Senior Housing News. The average age of senior housing stock in the 31 primary markets tracked by NIC was 21 years in the third quarter of 2019. Buildings between 10 and 17 years old are in peak ranges for peak occupancy and performance, Peck noted.

The exact reasons for this are various, but it’s likely that the first couple years are focused on lease-up, followed by a period where providers are still getting their feet on the ground and building a reputation in the neighborhood. Then, they hit their stride.

“[Buildings] between 10 and 17 years have built up [operational and staff] efficiencies to keep resident satisfaction high and word of mouth good,” Peck said. NIC’s data also found that younger markets with occupancy pressures such as Houston, Atlanta, Las Vegas and Denver also have some of the highest levels of new inventory growth. In these markets, such as Houston, it is actually the newer inventory dragging down the overall occupancy numbers, Peck noted in a NIC Notes post on Wednesday.

The data suggests that a lack of new supply allows developers and communities to meet market demand without having to invest in wholesale renovations. As new inventory comes online in mature markets, however, communities with available resources should be able to maintain occupancy if they are proactive and strategic in how they invest CapEx and reposition their properties.

Casa de Las Campanas is one example. This continuing care retirement community in Rancho Bernardo, California, received its first move-ins in the mid-1980s and was the only community of its kind in its market near San Diego for nearly 20 years. Indeed, San Diego is one of the oldest senior housing markets in the country in terms of the average age of its properties.

Five years ago, the Casa de Las Campanas board decided it needed to reposition the community in order to compete with new competition in the market and enlisted LCS Development to help draft a master plan to update its campus and maintain its share in the market, LCS Development Senior Vice President/Director of Project Development Ted MacBeth told SHN. The Des Moines, Iowa-based developer is part of Life Care Services, Casa de Las Campanas’ longtime operator. Members of the community’s board initially approached LCS about ways to reposition the campus during a retreat.

“[The board were] concerned about emerging competition and felt the community was showing its age. They asked us to conduct a master plan so that it could maintain its relevancy in the market,” he said.

LCS Development’s assessment of Casa de Las Campanas’ campus determined several issues. Amenities were modest, poorly situated and outdated to meet demand. The community was built into a hill — units and common areas faced inward, away from natural light . The original health center was antiquated and undersized to meet the modern needs of its residents. And there was no purpose-built assisted living; independent units were converted into assisted living over the years but were inadequate to meet the needs of residents.

LCS Development crafted a four-phase redevelopment plan for Casa de Las Campanas, Project Development Manager Ross Nichols told SHN. The first phase, now completed, involved relocating the salon and art room near the community’s entrance, tearing down a bank teller office, and building a bistro in their place. The bank teller was replaced with a more convenient ATM, and an antiquated convenience store was into the bistro, offering a la carte services.

This allowed LCS to integrate the spaces, create new communal space for seating and congregation, and allow natural light to enter.

“[Casa de Las Campanas] were doing a good job of maintaining what they had. They weren’t replacing what they had,” Nichols said.

The second phase of repositioning — the construction of a new health center on the former site of staff parking — is nearing completion. It will include 72 units, most of them private. Phase III involves razing the old health center and building a new five-story mixed-use building including 50 independent living units, 44 assisted living units and 22 memory care units, along with a library, theater, multipurpose space and resident lounges.

Not all boards are as attuned to market conditions, Cain Brothers Managing Director Bill Pomeranz told SHN. The New York City-based investment bank advises, and provides debt and equity to, nonprofit and for-profit long-term care providers and developers.

Pomeranz sees nonprofit providers, in particular, lagging behind their for-profit counterparts in developing repositioning plans.

“Our experience that there is a number of [nonprofit communities] that are older and antiquated, thinking those are still high-end, middle class-sites when they aren’t. Now they are struggling to stay competitive with obsolete product,” he said.

No risk incentive

The view is emblematic of the larger pattern within the nonprofit space to explore new markets to build, or to reinvent their existing communities, which Pomeranz classifies as a lack of incentive for risk on the part of boards and CEOs.

“A board doesn’t reward you to take a risk if you’re a CEO. Many CEOs feel this is the best job they’ll get and why shake things up,” he said.

Last month, Cain Brothers and Chicago-based health care industry consultant 4Sight Health published a report exploring how developers and providers can repurpose tired and underperforming long-term care facilities into new uses, notably affordable housing.

As advancements in home health care allow seniors to age in place more gracefully in their homes, affordable housing is one option providers should consider, 4Sight Health CEO David Johnson told SHN. This proposal ties into the fact that components of the CCRC model such as skilled nursing are ripe for repositioning. This product was built to meet a specific need in target markets that is no longer there, as a result of demographic shifts. Yet the demand for middle-market and affordable housing will continue to grow, and there is an opportunity to repurpose underused buildings to meet that demand.

The problem is particularly acute with faith-based providers.

“A SNF was built to serve a specific population that is now gone. The religious basis is not there,” Johnson said.

Favorable lending environment

Nonprofits’ aversion to risk — and repositioning communities to meet greater, future need — comes amidst one of the most favorable lending environments in recent memory. Well capitalized providers are well-positioned to take advantage of the lending environment but are not, Pomeranz told SHN.

A contributing factor to this is investment banks promoting favorable credit ratings because it is easier to sell debt. For-profit providers and developers can move forward with repositionings while only having weeks of cash reserves on hand in the event of an operational downturn. Nonprofits, on the other hand, may be sitting on a year or more of cash reserves.

Pomeranz believes well capitalized, multi-site nonprofit providers should entertain alternatives to bond financing to fund repositionings of lesser performing segments, such as agency debt, and deploy the tax-exempt financing to the well-performing segments.

“So many nonprofits are addicted to tax-exempt debt,” he said.

Placing agency debt on non-core product allows for more upward cash flow and the flexibility to do more creative things with mid-performing properties. The cash-to-debt ratios of agency tronches are split between parent organization and the facilities that don’t have those applied to them.

“Nonprofits need to think about their balance sheets differently,” Pomeranz said.

CCRCs, particularly in more urban infill locations, may be able to access other funding mechanisms such as low income housing and new market tax credits. But the market for these credits is competitive, and some states like California provide density bonuses for senior housing renovations, compared to a pure multifamily development.

Opportunity zones are another option, and inventive developers will find ways to leverage their redevelopments to tap into these funds as the guidance for opportunity zone funds evolves, Johnson said.

“It’s a way for the cities creating the zones to make neighborhoods more vibrant. Each project and neighborhood is specific,” he said.

Companies featured in this article:

4Sight Health, Cain Brothers, LCS Development, Life Care Services, National Investment Center for Seniors Housing & Care