While some markets in the U.S. are undergoing periods of senior housing oversupply, much of Canada is experiencing the opposite

Specifically, Canada is facing a “severe housing shortage” for older adults, according to new research from global credit rating agency DBRS. The report, “Analyzing the Canadian Senior Housing Dilemma,” is based partly on recent senior housing figures compiled by the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC).

Like the U.S., Canada has a rapidly growing population of older adults. The number of Canadian seniors is expected to surpass the number of Canadian children age 14 and younger by the year 2021, according to a Statistics Canada report cited by the DBRS researchers. By 2036, seniors in Canada could number between 9.9 million and 10.9 million.

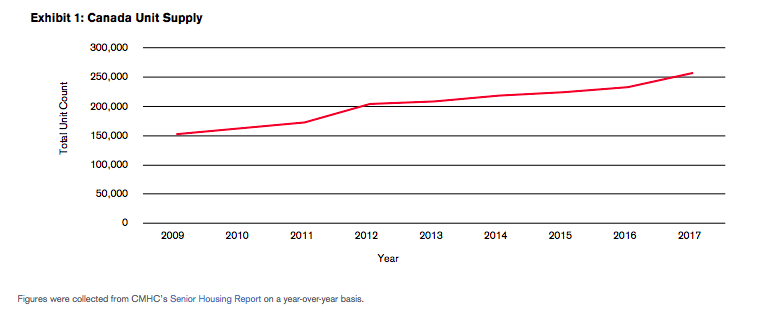

There were about 258,000 senior housing units in Canada last year, according to the CMHC. New supply growth clocked in at approximately 6.9%, year-over-year, between 2009 and 2017. At the same time, Canada’s senior population grew by an average of 21.7% in the decade between 2006 and 2016, which is more than double the rate of the supply increase.

The growing number of Canadian seniors, coupled with fewer new senior housing units, has helped lead to low vacancy and rising rent at many of the country’s retirement communities. The national vacancy rate for Canadian senior housing communities was 7.8% as of 2017, while the average rental rate grew 4.7%, year-over-year, between 2013 and 2017. By 2025, national average rental rates in Canada could hit around C$4,000 per month.

These issues are exemplified by some of the senior housing properties that DBRS rates. Those properties have an average occupancy rate of 95.1% and an average rent of around C$3,552, according to the agency.

Still, solving the problem won’t be as easy as simply building more communities. For one, there are more regulations in Canada than in countries like the U.S. that govern property development, which can make it harder for investors to build and manage senior housing properties.

“Some of these regulatory requirements include minimum staffing, number of services offered (like a meal service, transportation, etc.), personal support worker program, etc. These were some of the regulations implemented in Québec in 2013,” the report noted. “Regulatory trends may slow down unit development or give a greater preference toward independent property units, which require much less regulation.”

Access the full report on the DBRS website.

Written by Tim Regan